I can pinpoint the exact moment Led Zeppelin IV rewired my teenage brain. November 1984, sophomore year of high school. I was at my friend Tony’s house – this was the guy who’d already introduced me to Black Sabbath and Deep Purple, functioning as a one-man classic rock education system for my Kiss-and-Iron-Maiden-fixated young mind.

“You need to hear this,” he said with a gravity usually reserved for announcing deaths or pregnancies. He pulled out this weird album with no title or band name, just four cryptic symbols on the cover. “Sit down. Don’t talk.”

He dropped the needle on his dad’s turntable – this beautiful vintage Technics that I coveted with the burning passion of a thousand suns – and the opening acoustic notes of “Black Dog” filled the room.

Wait, that’s not right. “Black Dog” doesn’t start acoustic. But that’s what I THOUGHT I was hearing, because like most kids in the ’80s, I’d only ever caught fragments of Zeppelin on the radio. I had no context, no full album experience. When those crushing electric guitar chords hit and Robert Plant’s banshee wail cut through everything, I physically jumped. Tony just nodded, knowing exactly what was happening to me.

That was 41 years ago, and I’ve since listened to Led Zeppelin IV approximately eleventy billion times (scientific estimate). By all rights, I should be completely sick of it. Every note, every drum fill, every Plant “baby baby” should trigger an eye-rolling “this again” response. But it never happens. Each listen somehow reveals new details, new appreciation, new magic – like the album exists in some weird quantum state where it’s simultaneously intimately familiar and constantly surprising.

What is it about this album that allows it to defy the law of diminishing returns? I’ve thought about this question embarrassingly often – like, enough that several ex-girlfriends have cited “talks about Led Zeppelin IV too much” as a contributing factor to our breakups. (In my defense, if they’d really LISTENED to “Going to California,” they would have understood).

Part of the album’s enduring power is its perfect blend of seemingly contradictory elements. It’s heavy but delicate, mystical but earthy, complex but accessible, technically impressive but emotionally raw. Side one moves from the strutting sexuality of “Black Dog” to the folk-infused “Rock and Roll” (ironically the least traditionally rock and roll track title possible), then drifts into the mandolin-driven beauty of “The Battle of Evermore” before culminating in “Stairway to Heaven,” which I promise I’ll discuss in a non-eye-rolling way in a minute.

Side two opens with the thunderous swagger of “Misty Mountain Hop” (my personal favorite track, which I’m pretty sure makes me weird), transitions to the haunting blues of “Four Sticks,” then gives us the acoustic perfection of “Going to California” before ending with the primal, apocalyptic “When the Levee Breaks.”

That’s a masterclass in pacing and contrast. No two songs occupy the same emotional or sonic territory, yet they’re all unmistakably Zeppelin. The band was firing on all cylinders, having mastered both the bulldozer heaviness that defined their early work and the folk and world music influences that would characterize their later albums.

I went through a phase in college where I would literally plan my day around Led Zeppelin IV. Monday morning class? Start with “Black Dog” to get the energy up. Studying in the afternoon? “The Battle of Evermore” created the perfect background atmosphere. Heading to a party Friday night? “Rock and Roll” was the mandatory primer. Getting over yet another failed relationship attempt? “Going to California” on repeat until my roommate threatened violence.

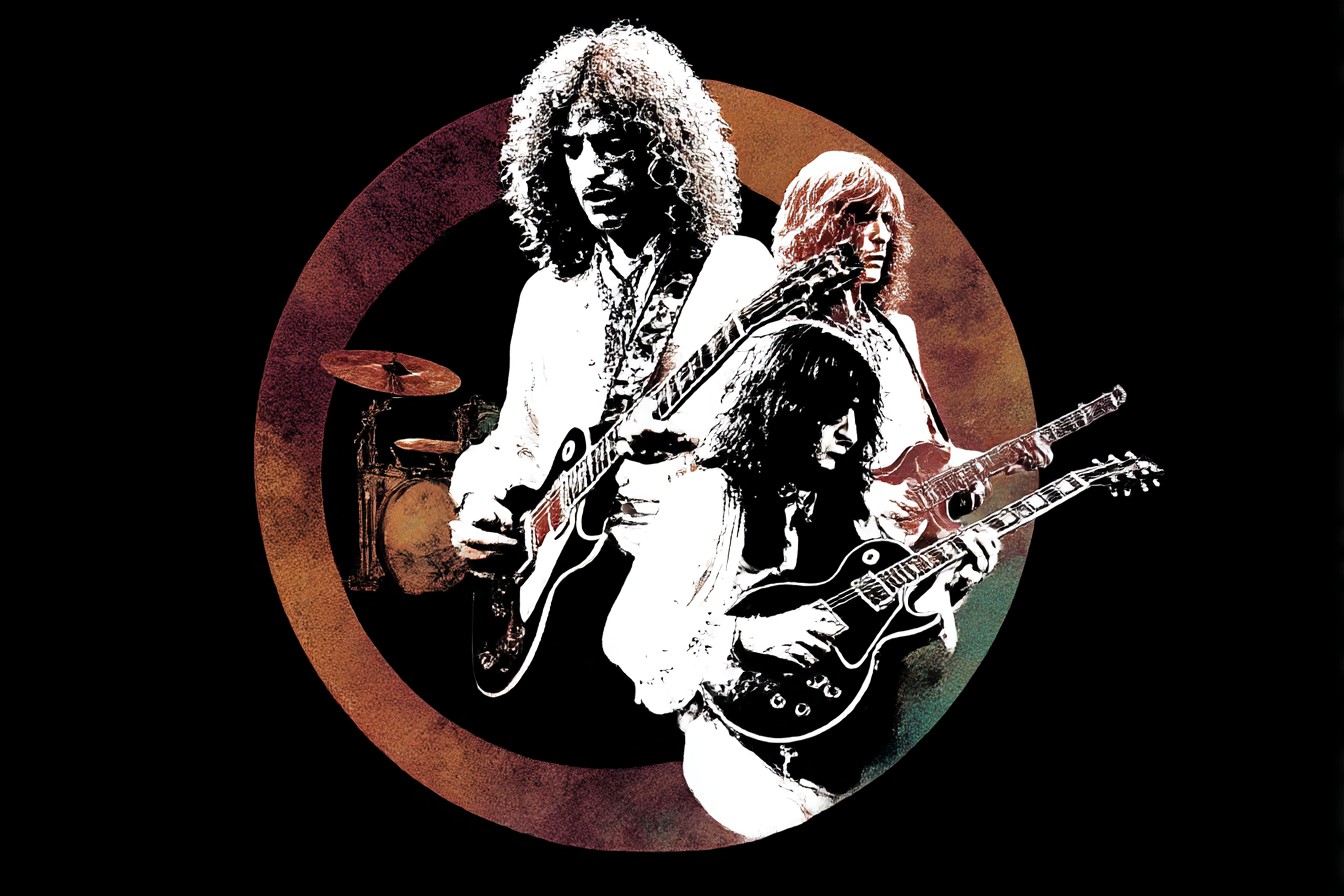

Let’s address the 8-minute mystical elephant in the room: “Stairway to Heaven.” No song has suffered more from overplay, parody, and “Anyway, here’s Wonderwall” guitar store mockery. It’s become almost impossible to hear it with fresh ears. But strip away all the cultural baggage, and what remains is a genuine masterpiece of composition. The gradual build from acoustic delicacy to full-band intensity. Jimmy Page’s perfectly constructed solo. John Bonham’s restrained-until-it-isn’t drumming. John Paul Jones’ understated bass work that somehow holds the whole thing together.

I interviewed Jimmy Page once – very briefly, at a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame event where I somehow talked my way backstage with press credentials that were, let’s say, creatively interpreted. I had about 45 seconds before security figured out I didn’t belong there, and instead of asking something profound about composition or guitar technique, I blurted out: “Do you ever get tired of hearing ‘Stairway’?”

He gave me this look that was equal parts amusement and weariness and simply said, “I never tire of hearing what we created. I tire of bad imitations.” Then security escorted me out, but I got my quote, dammit.

The production on IV deserves special attention. This album somehow sounds both vintage and timeless. Unlike many early 70s albums that scream “THIS WAS RECORDED IN 1971!” with dated production techniques, Led Zeppelin IV exists in its own sonic universe. Listen to the room sound on Bonham’s drums in “When the Levee Breaks” – recorded in a stairwell at Headley Grange with microphones dangling from several stories above. That thunderous, cavernous sound has been sampled hundreds of times by everyone from the Beastie Boys to Beyoncé, yet the original still hits harder.

The album’s mysticism is another key to its longevity. From the cryptic symbols representing each band member to the Tolkien references in “The Battle of Evermore” and “Misty Mountain Hop” to the haunting photo of the old man with sticks on the inner sleeve, there’s a whole mythology to unpack. Teenage me spent countless hours analyzing lyrics and imagery, convinced I was on the verge of unlocking some profound cosmic secret. Adult me realizes that’s exactly what they wanted – the album is designed to feel like an ancient text revealing itself slowly over repeated listens.

I have distinct memories attached to each song. “Four Sticks” playing on my Walkman as I nervously waited for my first real job interview at Record World in 1988. “Going to California” drifting from my dorm room speakers the night I decided to drop out of college and pursue music journalism full-time (sorry, Mom and Dad). “When the Levee Breaks” blasting from my car stereo as I drove cross-country to my new life in Seattle in 1996, feeling like I was in a movie about someone cooler than me.

The album’s influence is so vast it’s almost impossible to measure. Without IV, would we have had the folk-metal explorations of bands like Opeth? The mystical side of Iron Maiden? The acoustic-to-electric dynamics that became a staple of 90s alternative rock? The blues-based heaviness that informed the entire stoner rock movement? It’s like a musical Rosetta Stone that unlocked possibilities for generations of musicians.

I’ve owned this album in every format imaginable – vinyl (three different pressings), cassette (wore out two copies), CD (original and remastered), digital, and most recently, the deluxe vinyl reissue that cost more than my first car. Each version has revealed different nuances, different textures, different ways into these songs I thought I knew by heart.

My current ritual involves playing the album on Sunday mornings while making breakfast – the perfect soundtrack for coffee brewing and pancakes sizzling. My girlfriend, who’s 15 years younger than me and grew up on 90s alt-rock, recently asked, “Don’t you ever get tired of this album?” I just smiled and handed her a cup of coffee. “That’s like asking if I ever get tired of breathing,” I replied, immediately recognizing how pretentious that sounded. But it’s true – at this point, Led Zeppelin IV isn’t just music I listen to; it’s become part of my internal operating system.

Every generation discovers this album anew. I remember the first time I played it for my nephew, watching his face when “Black Dog” kicked in. The same wide-eyed “what IS this?” expression I must have had in Tony’s bedroom all those decades ago. The timelessness of it hit me then – how these four British guys managed to create something in 1971 that still sounds fresh and powerful and mysterious to ears encountering it for the first time in the 2020s.

Maybe that’s the true magic of Led Zeppelin IV – it exists outside of time, a perfect capsule of creativity that somehow never ages, never diminishes, never fully reveals all its secrets no matter how many times you revisit it. It’s the rare album that becomes more rather than less with familiarity, like an old friend who still surprises you after decades of conversation.

So yeah, I’ve heard “Stairway to Heaven” approximately 10,000 times, and I’ll probably hear it 10,000 more before I’m done. And you know what? That’s just fine by me. Some things never get old, no matter how many times you’ve heard them. Led Zeppelin IV isn’t just one of those things – it might be the definitive example.

Leave a Reply