July 1996. I was sitting in the offices of Riff Raider, sorting through the week’s new releases, when I pulled out Sublime’s self-titled album. The cover—a simple blue-tinted photo of a Dalmatian named Lou Dog set against a plain background—gave little indication of the musical alchemy contained within. What struck me immediately was the small text beneath the band name: “In memory of Bradley Nowell 1968-1996.”

I’d been vaguely aware of Sublime through their underground hit “Date Rape” and had heard murmurs about the lead singer’s death from a heroin overdose, but I hadn’t connected the dots until that moment. This wasn’t just a new album; it was a posthumous release, the final testament of a voice silenced too soon. Bradley Nowell had died on May 25, 1996—exactly one week after the album’s completion and two months before its release. He would never know that the record he’d poured his soul into would eventually go five-times platinum and define a uniquely Californian sound for an entire generation.

My first listen was a revelation. This wasn’t punk, wasn’t reggae, wasn’t ska, wasn’t hip-hop, but somehow it was all of those things simultaneously. Songs like “What I Got” and “Santeria” seamlessly blended genres that rarely interacted, creating something that felt both innovative and oddly familiar, like remembering a place you’d never actually been. I immediately called my editor and insisted on covering the album, sensing that something significant had emerged from the laid-back Long Beach scene.

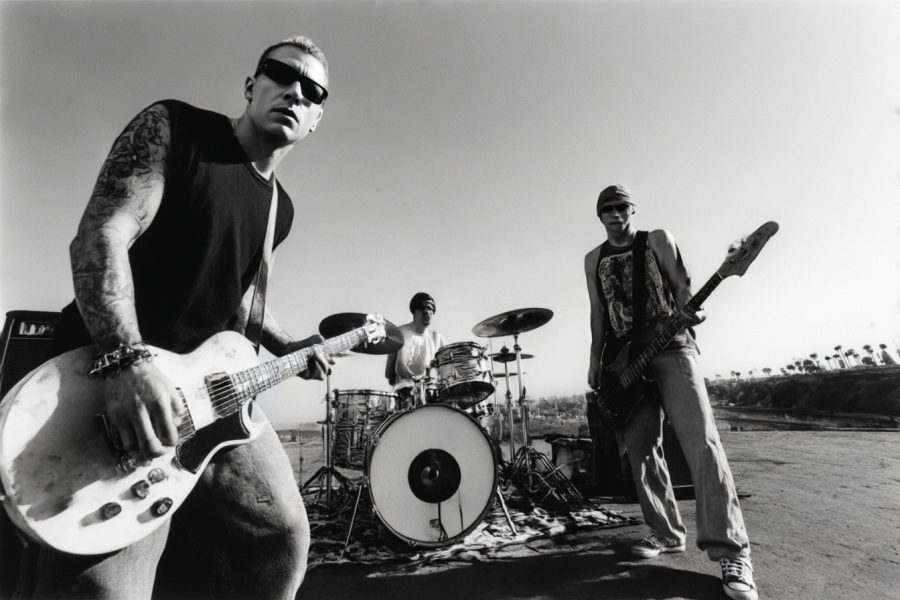

Sublime’s self-titled third album represents one of music’s most bittersweet success stories. A band that had built a devoted regional following through relentless touring and two independent releases (“40oz. to Freedom” and “Robbin’ the Hood”) had finally crafted their definitive statement—only for their focal point to check out just as they were poised for breakthrough success. The album would go on to launch hit singles, soundtrack countless parties, and influence a wave of bands, but the trio that created it would never perform these songs together.

The album’s creation was nearly as chaotic as its sound. Produced by Paul Leary of the Butthole Surfers (an inspired choice), the recording sessions were reportedly hampered by Nowell’s escalating heroin addiction. The band would sometimes lose days to his habit, then capture magic in brief windows of clarity. That tension—between dysfunction and inspiration—permeates the record, giving even its most upbeat moments an undercurrent of fragility.

I eventually interviewed bassist Eric Wilson in late ’97, when the album had become an unexpected smash and the band’s legacy was being cemented in real-time. He was still processing the whiplash of it all—the tragedy of losing his friend juxtaposed against the album’s growing success.

“Brad would have fucking loved this and hated it at the same time,” he told me, lighting a cigarette in the small backstage room where we sat. He was touring with the Long Beach Dub Allstars at that point, keeping the musical spirit alive while acknowledging it could never be the same. “He always wanted Sublime to blow up, but he was also scared of what that would mean. I think about him every time I hear one of our songs on the radio. It’s like… he’s everywhere now, but he’s gone.”

That paradox defines the album’s legacy. Nowell’s absence hangs over every note, yet his presence is so vivid in these tracks that he feels tangibly alive within them. His vocal performances—by turns soulful, playful, aggressive, and vulnerable—convey a charisma that transcends the tragedy of his fate. When he sings about his struggles on “Under My Skin,” the knowledge of what was to come gives his words extra weight, but the performance itself is so vibrant that it temporarily suspends that reality.

What made “Sublime” connect so powerfully beyond the band’s existing fanbase was its accessibility without compromise. These weren’t watered-down versions of the band’s earlier sound; if anything, the album represented a more fully realized vision of what they’d been working toward. Songs like “Wrong Way” and “Santeria” packaged complex emotional content—tales of prostitution, revenge, heartbreak—in deceptively catchy melodies and grooves. You could dance to these songs without fully processing their darkness, or you could dive deeper and find layers of meaning.

The band’s genre-blending approach perfectly captured a specific Californian sensibility. Growing up in Southern California meant being exposed to an eclectic soundtrack—punk from Hermosa Beach, hip-hop from Compton, reggae and ska filtering in through the beach communities, Latin rhythms from the state’s Mexican heritage. Most bands might incorporate one or two of these influences; Sublime absorbed them all, creating a musical gumbo that felt authentic because it reflected the actual cultural melting pot they came from.

I saw this cross-cultural appeal firsthand when covering the first Smokin’ Grooves tour in summer ’96. The predominantly hip-hop lineup (The Fugees, Cypress Hill, A Tribe Called Quest) had added “What I Got” to the between-set playlist after it started gaining traction. The crowd’s reaction was fascinating—frat boys, hip-hop heads, punks, and metal kids all responding with equal enthusiasm. The song seemed to erase tribal divisions, if only temporarily.

The production of the album deserves special credit for this broad appeal. Paul Leary and engineer Stuart Sullivan managed to create a sound that honored Sublime’s rawness while giving it enough polish to translate to wider audiences. The drums hit with proper weight, the bass has room to breathe, and Nowell’s guitar work—an underrated aspect of his musicianship—cuts through with clarity. Unlike many punk-adjacent albums from the ’90s, it doesn’t sound dated or thin decades later.

The songs themselves showcase extraordinary range. “Garden Grove” opens the album with a hip-hop beat and Nowell speak-singing over a dub bassline before exploding into punk energy. “April 29, 1992” addresses the LA riots with journalistic detail over a reggae groove. “Caress Me Down” incorporates Spanish verses and a Lover’s rock sensibility. “Same in the End” could be a lost Descendents track. This diversity could have resulted in a disjointed mess, but Nowell’s distinctive voice and perspective provided the connective tissue that made it feel coherent.

What’s often lost in discussions of Sublime’s music is how lyrically sharp Nowell could be. Behind the party-friendly veneer and sometimes problematic content were moments of genuine insight and self-awareness. He could be crude and juvenile, certainly, but he could also turn that same unflinching gaze on himself, particularly regarding his addiction. There’s a raw honesty in lines about his struggles that feels miles removed from the calculated angst that dominated alternative rock at the time.

The most haunting aspect of the album is how clearly it points toward creative directions that would never be explored. This wasn’t a band reaching the end of their creative rope; this was a group just hitting their stride, discovering the full possibilities of their sound. The final track, “Doin’ Time,” with its Gershwin interpolation and trip-hop influences, hints at avenues that Sublime might have explored had fate taken a different turn.

I found myself thinking about this lost potential while attending a Sublime with Rome show in 2010. Rome Ramirez was a capable vocalist who clearly revered the material, but watching him perform these songs drove home what had been lost. Nowell’s voice—both literally and figuratively—was irreplaceable. His specific fusion of influences, his particular perspective, his singular charisma couldn’t be replicated, no matter how faithfully the notes were played.

Yet the music endures, finding new audiences who have no firsthand memory of the band’s actual existence. Walk through any college campus in America, and you’ll still hear “Santeria” or “What I Got” drifting from dorm windows. The album’s appeal has transcended its era, becoming one of those rare records that seems to be discovered anew by each generation of listeners.

This endurance speaks to something universal in Sublime’s hybrid sound. By refusing to respect genre boundaries, they created music that appeals to people who might otherwise never find common ground. The skater who loves punk, the hip-hop head drawn to the beats and samples, the reggae enthusiast appreciating the authentic dub elements—all can find something to connect with. In our increasingly fragmented musical landscape, this cross-cultural appeal feels more significant than ever.

Last year, on a trip to Long Beach, I made a pilgrimage to Nowell’s memorial—a modest plaque in Westminster Memorial Park. Among the flowers and trinkets left by fans was a weathered cassette of the self-titled album, somehow both poignant and fitting. That little plastic rectangle contained the final testament of an artist who left us at 28 but whose musical vision continues to resonate decades later.

The tragedy of Sublime’s story is obvious—a life cut short, potential unfulfilled, a band unable to build on their breakthrough. But there’s also something beautiful about the purity of their legacy. They’ll never release a disappointing follow-up, never make awkward attempts to chase trends, never decline into irrelevance. They exist in amber, forever at their creative peak, their defining statement uncompromised by what might have come after.

In a career tragically bookended by his death, Bradley Nowell and Sublime created something that transcended their time and place even as it perfectly captured it—a sun-soaked, smoke-hazed, uniquely Californian fusion that continues to define what many people worldwide associate with West Coast culture. What began as a regional sound crafted by three friends from Long Beach became a global touchstone, an enduring testament to what happens when musical boundaries are ignored in favor of pure creative instinct.

“Sublime” stands as both epitaph and introduction—the end of a band’s journey and the beginning of their legend. Few albums carry such contradictory weight, simultaneously celebrating life while shadowed by death. But perhaps that’s why it continues to resonate so powerfully. In its grooves, Bradley Nowell remains eternally alive, his voice still cutting through the California haze, telling his stories with a clarity and authenticity that no amount of time can diminish.