The first time I heard “Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness,” I was sitting in the back room of Wax Trax Records in Chicago, October 1995. The owner, a guy named Terry with perpetually ink-stained fingers from handling too many record sleeves, had gotten an advance copy from the Virgin rep. Five of us crammed into this tiny space with a decent stereo system, passing around a bottle of cheap bourbon and a pack of cigarettes (because it was 1995 and indoor smoking bans weren’t yet a thing). Two hours and twenty-eight songs later, we stumbled out into the autumn night, ears ringing and minds blown, and Terry just said, “Well, shit. Corgan’s either made his ‘White Album’ or he’s finally disappeared up his own ass.”

That’s the thing about double albums – they exist in this precarious territory between ambition and indulgence. For every “Exile on Main St.” or “London Calling,” there’s a dozen bloated, self-important misfires that would’ve made killer single albums if someone had just had the guts to say “no” occasionally. But “Mellon Collie” somehow managed to be both sprawling AND focused, excessive AND essential. Twenty-eight tracks without a clear narrative throughline that nonetheless felt like a complete statement.

We didn’t know it at the time, but we were witnessing the last gasp of a particular kind of rock star excess that the CD era made possible. The kind of grand statement album that required the listener to commit to a two-hour journey with an artist’s complete vision. The kind of project that streaming services and playlists would eventually render nearly extinct.

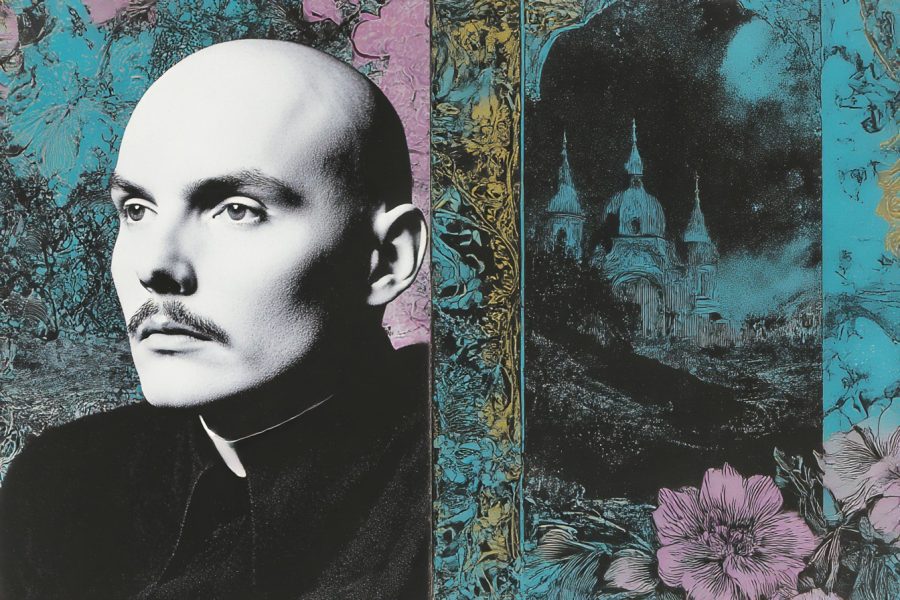

I interviewed Billy Corgan six months after the album’s release for a piece in Riff Raider. He showed up at this coffee shop wearing a ridiculous silver pants and a ZERO shirt, bald head gleaming under the fluorescent lights. The first thing I noticed was how exhausted he looked – pale and drawn, with dark circles under his eyes. This was about halfway through their mammoth world tour, and the strain was showing. We talked for nearly three hours, and what struck me most was his absolute certainty about what he’d created.

“I know exactly what this album is,” he told me, stirring his tea obsessively. “It’s everything I wanted to say before I turn 30, because who knows if I’ll even want to make rock music after that?” There was something both arrogant and vulnerable about the way he said it – like he knew how pretentious it sounded but couldn’t help himself.

The crazy thing is, he was right. “Mellon Collie” really is a comprehensive document of what it feels like to be in your late twenties, caught between youthful angst and adult resignation. From the gentle piano of the title track to the apocalyptic roar of “X.Y.U.,” the album swings between extremes in a way that shouldn’t work but somehow does.

I still remember the exact moment I realized the album was something special. It was during my third listen, alone in my apartment this time. “Porcelina of the Vast Oceans” was playing – that section where the gentle intro suddenly erupts into this massive wall of guitars – and I had this weird epiphany. Corgan wasn’t just making a double album because his ego demanded it; he was making one because the emotional terrain he wanted to cover genuinely required that much space. You couldn’t capture both the whispered intimacy of “Stumbleine” and the stadium-sized bombast of “Jellybelly” on a single disc without giving both short shrift.

“Mellon Collie” dropped at this fascinating cultural moment – grunge was effectively dead with Kurt Cobain’s suicide the year before, but alternative rock still ruled the airwaves. The Pumpkins had always existed slightly adjacent to the Seattle scene anyway, too theatrical and ambitious to fit neatly into the flannel-and-dismay aesthetic. This was their moment to plant their flag as something different.

And man, did they seize it. The album sold over 10 million copies, spawned five singles, and earned seven Grammy nominations. I remember walking through a mall in early 1996 and hearing “1979” playing in three different stores simultaneously. For a brief moment, this weird, sprawling art project had become the commercial center of rock music.

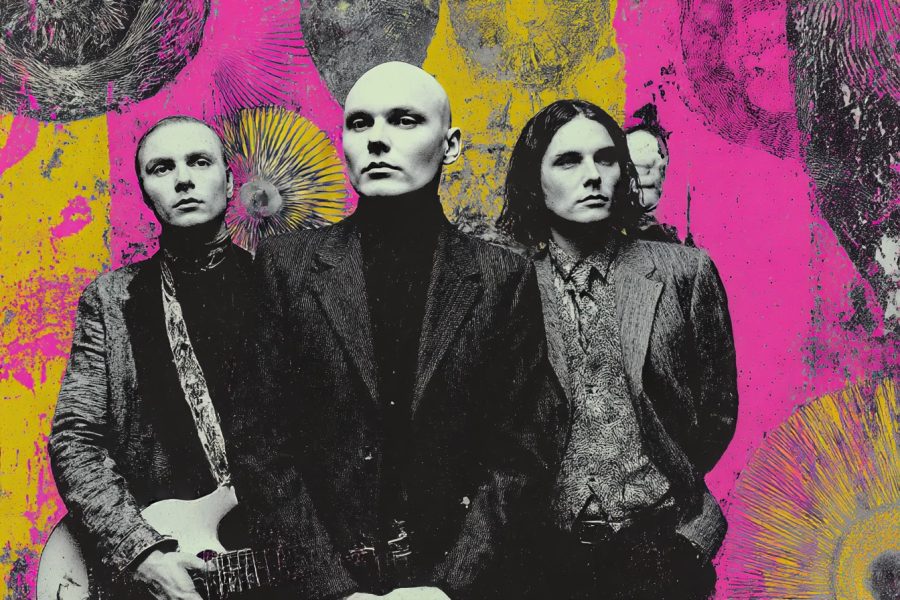

Which makes what happened next all the more tragic. The touring cycle for “Mellon Collie” was when everything started falling apart. Keyboard player Jonathan Melvoin died from a heroin overdose in July 1996, leading to drummer Jimmy Chamberlin being fired from the band. The interpersonal dynamics, already strained during recording (Corgan played most of the bass and guitar parts himself, despite having D’arcy Wretzky and James Iha in the band), fractured completely.

I ran into James Iha at Lounge Ax in Chicago during this period. He was watching this local band, standing alone at the bar. I’d interviewed him a couple times before, so I went up to say hello. He looked through me for a moment before recognizing me, then just sighed and said, “Hey man.” We chatted briefly, awkwardly, and I asked how the tour was going. He took a long pull from his beer and said, “It’s like being forced to attend your own funeral every night, except it lasts three hours and you have to play guitar.” Then he walked away. That was it. The whole conversation.

In hindsight, “Mellon Collie” wasn’t just the peak of the Pumpkins’ career; it was the beginning of the end for the original lineup. By the time they released “Adore” in 1998, they were essentially a different band – more subdued, more electronic, missing Chamberlin’s thunder and carrying the weight of all that had happened.

What’s fascinating about the album is how it managed to be so many contradictory things at once. It was pompous yet sincere, calculated yet raw, retro yet forward-looking. Tracks like “Thirty-Three” and “1979” pointed toward the more mature, textured direction Corgan would explore later, while songs like “Tales of a Scorched Earth” and “Bodies” delivered the heaviest, most aggressive material the band ever recorded.

The album was packaged as this grand song cycle, divided into “Dawn to Dusk” and “Twilight to Starlight” discs, suggesting some kind of conceptual framework. But honestly, that was mostly marketing bullshit. Corgan later admitted the sequencing was determined largely by what would fit on each CD rather than thematic concerns. Yet somehow, the album flows beautifully, each song a distinct mood but part of a larger tapestry.

I used to have this ritual with “Mellon Collie” during my early years as a music writer. Whenever I got stuck on a piece, couldn’t find the right words, I’d put on disc two, skip to “Thru the Eyes of Ruby,” and just let that swirling wall of guitars (supposedly 70 guitar tracks layered together) wash over me. There’s something about its grandiosity that reminded me why I loved music enough to write about it in the first place.

The late ’90s would bring bands like Radiohead who took rock in more experimental directions, and by the early 2000s, the idea of a rock band releasing a sprawling double album as their commercial breakthrough seemed increasingly unlikely. The economics of the music industry were changing, attention spans were shortening, and the album as a format was beginning its long decline in cultural importance.

But for that brief moment in 1995-96, the Smashing Pumpkins managed to make a double album that was both an artistic statement and a commercial juggernaut. They threw everything they had into it – every style from metal to folk, every production trick in producer Flood’s considerable arsenal, every lyrical theme from cosmic romance to suicidal despair. The miracle is that it mostly worked.

I interviewed producer Flood years later for a piece on landmark ’90s albums. When I brought up “Mellon Collie,” he just shook his head and laughed. “That album nearly killed me,” he said. “Billy would be there at the crack of dawn with twenty new ideas, then still be there at midnight arguing about snare drum sounds. I’ve never seen someone so maniacally driven.” He paused, then added, “But you know what? When someone cares that much, when they’re willing to drive themselves and everyone around them to the breaking point because they believe so completely in what they’re doing… sometimes you get magic.”

That’s what “Mellon Collie” was – magic born from obsession, excess born from ambition. I’ve had arguments with fellow music writers about whether it would have made a better single album. You could certainly make a killer 12-14 track version. But that would miss the point entirely. The sprawl IS the statement. The fact that it contains multitudes – from the delicate beauty of “Cupid de Locke” to the industrial fury of “X.Y.U.” – is exactly what makes it special.

The Pumpkins would never reach these heights again. The subsequent “Adore” was a beautiful but commercially disappointing departure, and by the time 2000’s “Machina/The Machines of God” rolled around, the band was disintegrating. D’arcy left during recording, and the album’s convoluted concept and mixed reception effectively ended the group’s original incarnation.

I saw them on the “Machina” tour at the Aragon Ballroom, and it was a far cry from the triumphant “Mellon Collie” shows. The magic was gone, the energy dissipated. Corgan spent a good chunk of the show with his back to the audience, and there was this palpable sense of an era ending, of something once special now curdling before our eyes.

Last year, I found my original 2-CD copy of “Mellon Collie” while cleaning out a storage unit. The case was cracked, the booklet water-damaged, but I popped it into my car stereo anyway on the drive home. “Tonight, Tonight” came on with those sweeping strings, and I was instantly transported back to 1995, to that back room at Wax Trax, to that moment when rock music still felt world-conquering and limitless.

Double albums are dinosaurs now, artifacts from an age when artists could demand that level of attention from listeners. Even with streaming making album length irrelevant from a physical media standpoint, few artists ask for two hours of uninterrupted focus from their audience. We consume music differently now – playlists, algorithms, the endless shuffle.

But “Mellon Collie” stands as a monument to a specific moment when alternative rock briefly became the mainstream, when commercial success and artistic ambition could still align, when a band could throw absolutely everything at the wall and have most of it stick. It’s messy, overblown, occasionally ridiculous, and absolutely glorious – a sprawling testament to what happens when talent, ambition, and just the right amount of madness converge at exactly the right cultural moment.

Corgan once described the album as “The Wall for Generation X.” Typically grandiose statement, but not entirely wrong. It was the sound of a generation caught between ironic detachment and desperate yearning for connection, delivered by a frontman whose sneering ambition was matched only by his genuine belief in rock’s transformative power.

For better or worse, they really don’t make ’em like this anymore. And while part of me is grateful (god knows we don’t need more bloated double albums), another part misses the sheer audacity of it all – the willingness to risk looking foolish in pursuit of something genuinely monumental.

That night in the back room of Wax Trax, as the final notes of “Farewell and Goodnight” faded out, one of the guys – a cynical record store clerk who prided himself on hating everything popular – just whispered “holy shit” into his empty bourbon cup. Sometimes that’s all the music criticism you need.